Out and About – Visiting the Liverpool Biennial

Written by Amelia Kedge, ITP Assistant

We’ve been lucky with some beautiful sunny weather here in the UK over the past few weeks, and what better way to enjoy it than with a visit to Liverpool. Liverpool is a city in the North West of England, and holds a special place in my heart as it is where I went to university, so I am always excited for a visit back. Liverpool has the most museums and art galleries in the UK outside of London, and this year is hosting Liverpool Biennial, which I why I went to visit.

Founded in 1999, Liverpool Biennial is a visual arts organisation and a platform for commissioning and presenting contemporary art. The festival is a highly anticipated international event which transforms the city of Liverpool through public art commissions and community projects.

The 12th edition of Liverpool Biennial ‘uMoya: The Sacred Return of Lost Things’ addresses the history and temperament of the city of Liverpool and is a call for ancestral and indigenous forms of knowledge, wisdom, and healing. In the isiZulu language, ‘uMoya’ (pronounced oo-moy-ah) means spirit, breath, air, climate, and wind. Curated by Khanyisile Mbongwa, this years festival explores the way people and objects have the potential to manifest power as they move across the world, while acknowledging the continues losses of the past.

One of the recurring ways that ‘uMoya’ is interpreted across this year’s iteration, is through the city of Liverpool’s connection to the slave trade. Whilst enslaved people never passed through Liverpool’s docks, the ‘merchant’ ships that carried them were built there, and much of the city’s wealth came from slavery – read more about Liverpool’s links to the slave trade here. However, artists in the Biennial are tackling this subject with practices of repair, recur, and return; examining colonial histories and legacies, redrawing and remapping to create new possibilities and heal through knowledge and joy.

35 international artists and collectives have been invited to engage with the theme, taking over galleries, historic buildings, and unexpected spaces to create a 14-week programme of exhibitions, performances, screenings, and community events – all open to the public for free.

With such an extensive offering it was impossible to visit the entire programme in one day, so I headed to three of my favourite spaces in the city: The Tate Liverpool, The Bluecoat, and the Open Eye Gallery.

The Tate Liverpool was showcasing work by 11 artists, all acting as cartographers drawing or redrawing the lines of past catastrophes to create new possibilities. The exhibition opens with American artist Torkwase Dyson’s Liquid is a Place (2021), comprised of three striking structures representing the curved bow of a ship, each with a triangular void within to signify a gateway, a shelter, or the sailing route between Europe, West Africa, and the Americas. In the dimly lit room, and Tate Liverpool’s location right on the docks, the installation suggests that water can simultaneously be a place of resistance, fear, conflict, pollution, extraction, refuge, and liberation.

Upstairs, Edgar Calel’s Ru k’ox k’ob’el jun ojer etemab’el (The Echo of an Ancient Form of Knowledge) (2021) presents stones as sites of sacred ritual, laden with fruits and vegetables as offerings performed in a ritual during installation. Many cultures use food in religious or spiritual practices, and the ritual of cooking and sharing food with family or friends is practiced every day across the world. In Calel’s family, stories from dreams are shared over breakfast and are understood to foretell the energy for the day or task ahead. This work exists as an offering to the land and Calel’s Mayan Kaqchikel ancestors in Guatemala; to acknowledge, honour, preserve and be in the presence of ancestral indigenous forms of knowledge.

A slightly smaller venue, the Bluecoat presented works by 4 artists, including French artist Benoît Piéron, whose work considers the uncertainly or life, death, and immunity. Drawing on his own childhood experience spent in hospital, Le Lit (2011) is a hybrid hospital bed-come-tent, with the four posters made from bobbins of thread, and a paper chain barrier. Whilst the bed seems to have an eerie edge, with its real discarded hospital sheets and metal guttering rail, the work is a testament to play, and aims to reappropriate the hospital environment, presenting disease as a site of potential.

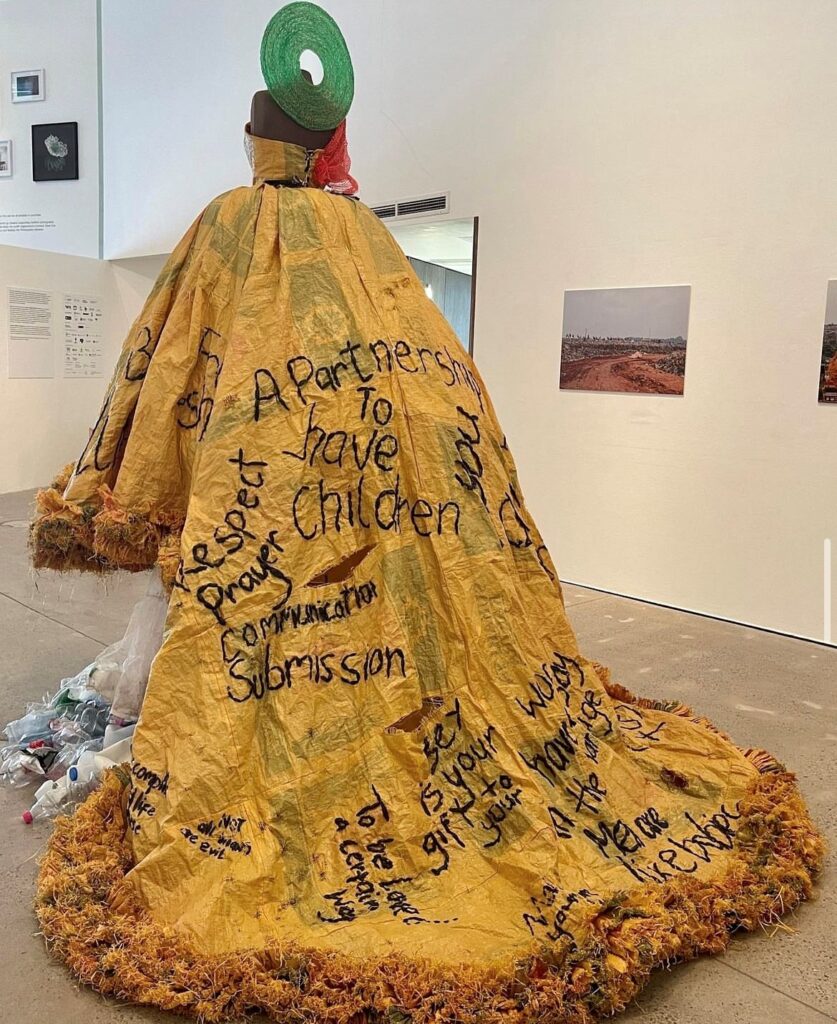

The Open Eye is a gallery predominantly dedicated to photography, and the 3 artists on display here use either film or photography as their medium. The standout piece for me was Ugandan artist Sandra Suubi’s Samba Gown (2021). Centre stage in the middle of the gallery, work is a statement of resistance which explores industrialisation, commodity, exploitation, material culture and women’s lived experiences. The dress, made of found plastic, is ‘stitched’ with opinions and stories from real women from Suubi’s local community who she engaged with to explore the expectations and realties of marriage in their culture. The installation is accompanied by a series of photographs of the dress being worn in a mock wedding procession, where the bride is pictured on rubbish dumps and surrounded by plastic waste – a comment on plastic pollution as one of the major aftermaths of colonialism.

Liverpool Biennial 2023 uMoya: The Sacred Return of Lost Things runs until 17th September