Learning From Other Museums and Galleries (Richard Ohene-Larbi, Ghana, ITP 2024)

Written by Richard Ohene-Larbi, Museum Educator, Ghana Museums and Monuments Board (Ghana, ITP 2024)

Dear gentle reader, today my blog is about activities undertaken during the Department Day with Julie Hudson and Helen Anderson, our ITP mentors. Julie and Helen took my colleagues (Doris and Lillian) and I outside the British Museum. The idea was to visit two museums in London to learn more about addressing sensitive topics and conflict.

First, we set off via bus to South London to visit the Second World War Galleries at the Imperial War Museum (IWM). As a museum professional, I have had several conversations with museum visitors and colleagues on their expectations of visiting a museum for the first time. One thing that cuts across is the name of the museum which often gives an idea of what that particular museum represents and how visitors may see it. The name Imperial War Museum hints at what is to be seen in the exhibitions and galleries. Indeed, the main entrance of the museum with the mounted pair of 15-inch naval guns creates a form of military ambience without scaring visitors. What crossed my mind was is the museum going to highlight the ‘glory and achievement’ of the British Empire? I somehow embraced myself to see a display of weapons and photographs of the victorious Allies of the Second World War.

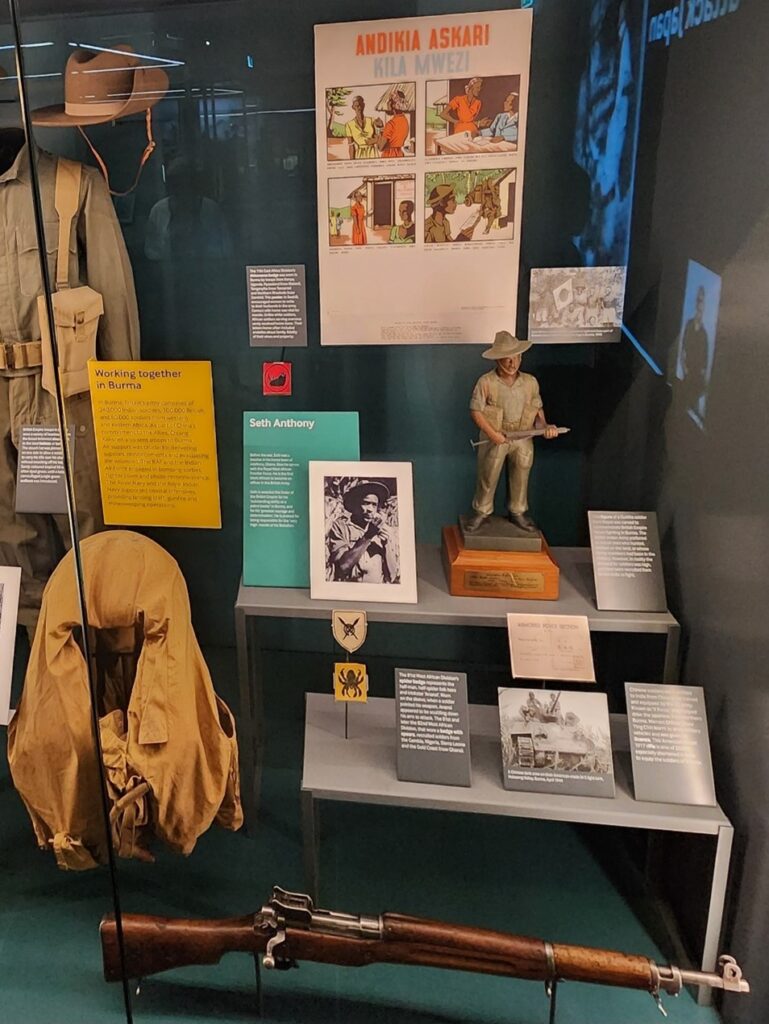

Whilst enjoying the beautiful park and sweet scents of the roses, we were met at the entrance by Vikki Hawkins, former Curator at the Imperial War Museum and current member of the Reimagining the British Museum Project. Vikki gave us a great tour of the Second World War Galleries. The questions asked and subsequent interactions broadened our understanding of how the exhibition was curated through research, collaborations with museum staff (from the IWM and other museums), families and people who in one way or another were involved in the war. I truly admired how the curatorial voice was silenced by allowing visitors to engage with the objects. The exhibition design, lighting, choice of colours, audiovisuals, sounds, graphics and maps brought to life the experiences of people from different backgrounds around the world. It was inspiring to see the contributions of Ghanaians (and Africans in general) acknowledged in the galleries. I learned about Seth Anthony, a Ghanaian teacher who joined the Royal West African Frontier Force and later became the first black African Officer in the British Army. Subsequently, he was awarded the Order of the British Empire for his courage, determination and outstanding ability as a patrol leader in Burma (now Myanmar). The story of Seth Anthony made me wonder whether his bravery and that of his fellow Gold Coasters (Ghanaians) played a role in the representation of Kwaku Ananse (a popular character often depicted as a spider in Ghanaian folklore) in the 81st and 82nd West African Divisions badge.

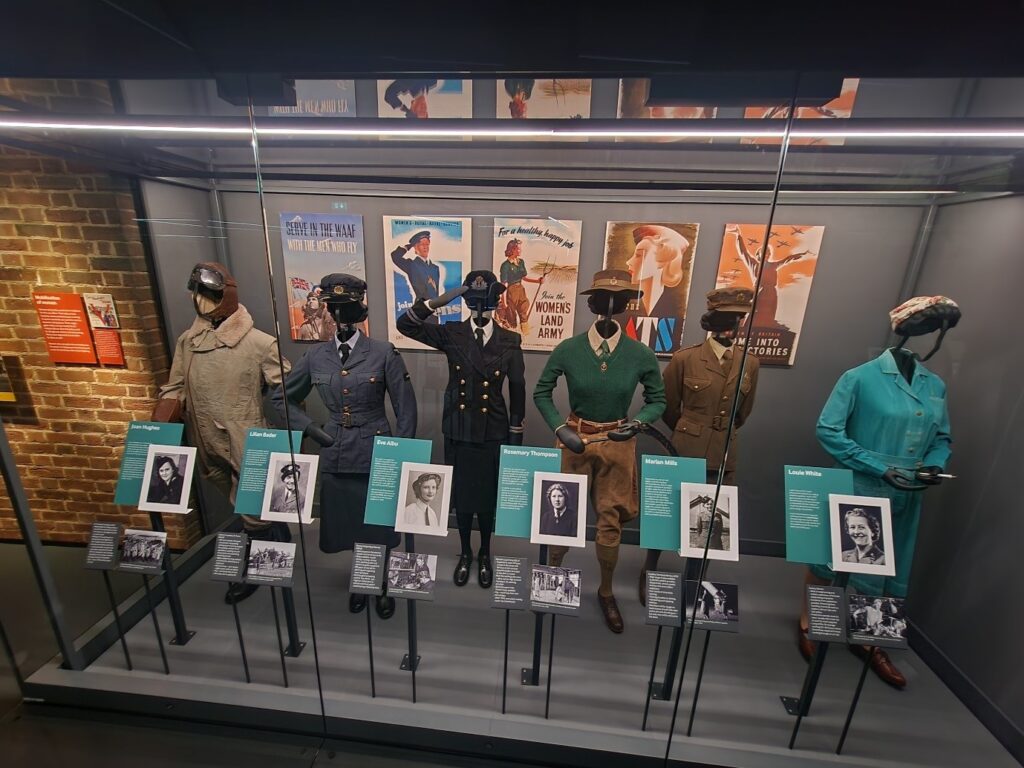

The contributions of women are often sidelined in war narratives, so it was refreshing to see them recognized. Thus, Britain conscripted women to join the armed forces, work on the land or industry. The experience gave me the chance to reflect on a session the ITP fellows undertook during the week on the representation of women in selected museums in London. The showcase with the women’s uniforms was so engaging that a visitor will understand why some women joined either the Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS) or Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF). Indeed, the beauty of a uniform was a strong pulling factor for the women to join a particular unit.

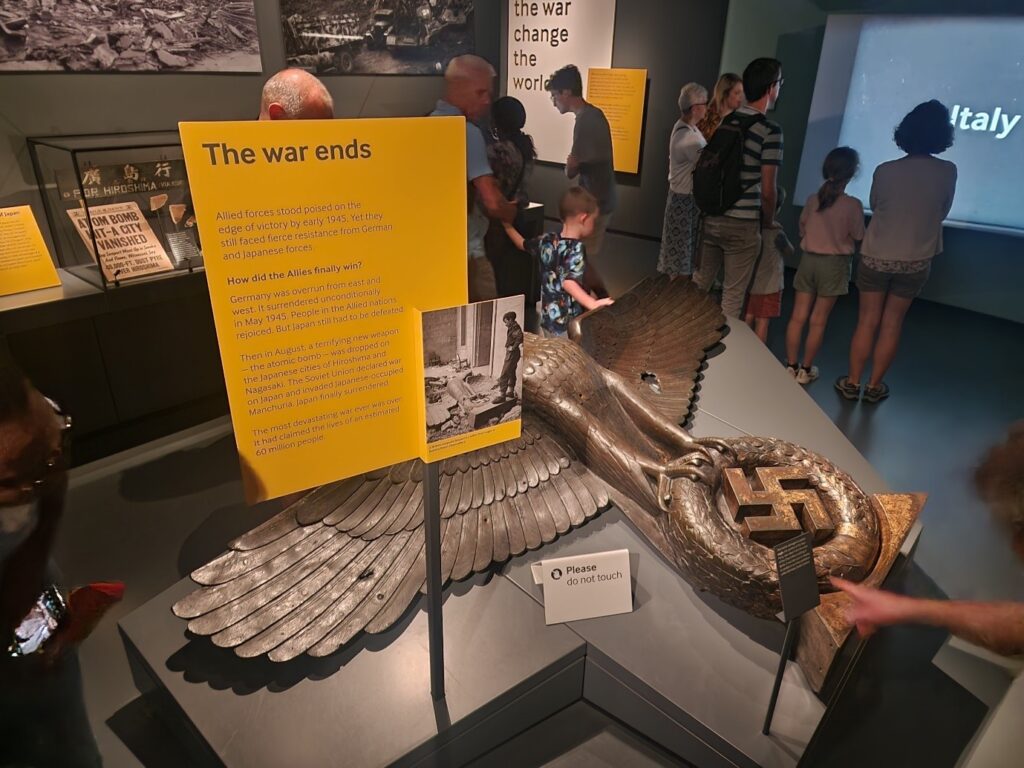

I must admit that contrary to the questions or my initial expectations, the Second World War Galleries rather gave a global perspective, and real-life stories of people involved from Africa, Asia, Europe, USA, etc without necessarily ‘glorifying’ the British Empire. It was an interactive way of telling the story of the war by showing how it started, where it was fought, those affected, the involvement of the British and the decline of the Empire after the war with the rise of independence movements from the colonies.

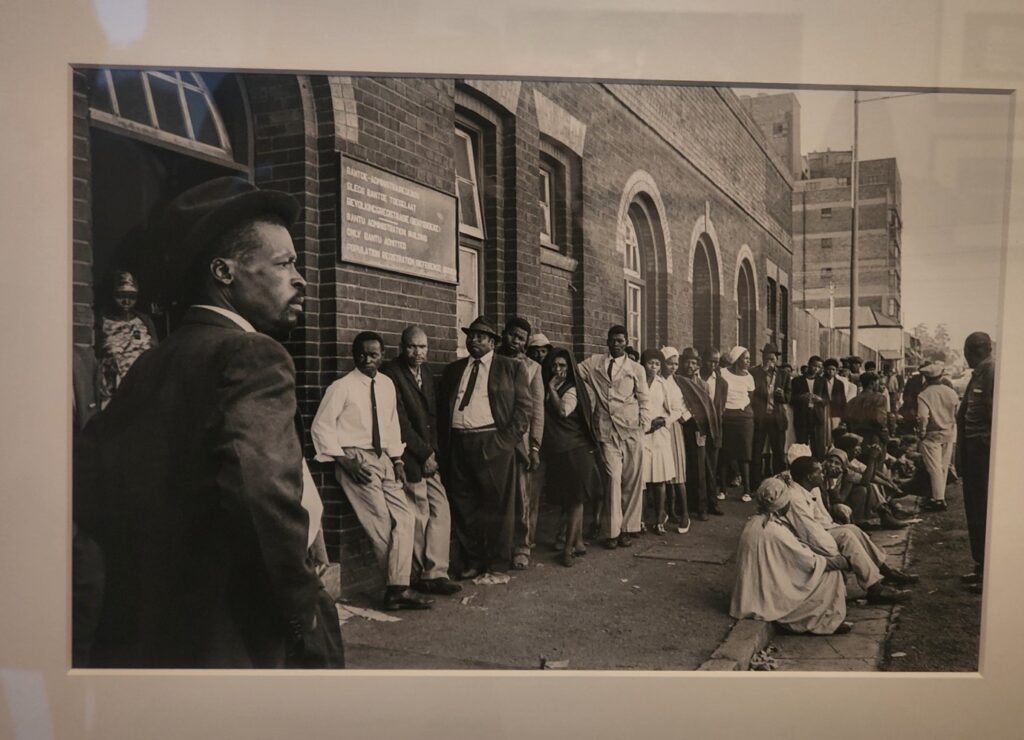

After lunch, we used the tube to get to the heart of London’s West End. This was to see the exhibition titled Ernest Cole: House of Bondage at the Photographers’ Gallery. The exhibition used several photographs from Ernest Cole’s photobook House of Bondage which was first published in 1967 to highlight the brutality and injustice of Apartheid as experienced by the Black population in South Africa. Some of the themes in the photographic exhibition included Black Spots, Pass Laws and Nightmare Rides.

The Black Spots were areas occupied by blacks that could be taken from them if the white population desired them. For example, a population of 25,000 could be wiped off the map and relocated to rural areas by the white government. The Pass Laws, on the other hand, restricted the movement of Black South Africans since they were arrested without it in white occupied neighbourhoods. As a result, many blacks queued at registration centres from 5:30am to get this pass as shown below. With or without this pass the average black person was considered a criminal suspect in Apartheid South Africa.

Again, the Nightmare Rides emphasized the issue of segregation through a series of photographs taken at a train station in Johannesburg. One could easily notice the difference between the platforms for blacks and whites. Other photographs showed how black South Africans were crowded on trains that were slow and full. This made their journeys to and from work very difficult. Indeed, the choice of plain backgrounds by the curator allows visitors to concentrate on the photographs without any distraction.

The day’s visits have helped me to learn more about curating conflicts and sensitive stories in museums.

I leave you in the capable hands of Roqaya Al Shokri, Head of the Information Department at the Oman Across Ages Museum, to write the next blog.

Medaase!